|

It is the last day of November. I’ve been watching the moon rise. It’s a full moon. The afternoon is already very dark. Over the course of the year, I’ve watched the Plough flip like a pancake across the horizon. Tonight there is lightning high up in the clouds, and it feels very neat and orderly that the last day of the month, before the last month of the year, is also the completion of this moon cycle. Since the hour shifted, I’ve been trying to chase the light - walking away from, then back towards the night, each dusk, wringing out the last of the day in one direction, where the sun is lowering and the sky becomes the colour of duck-egg blue and the yellow of the duckling within it; then turning home to grey and the moon. When environmental activist, Satish Kumar was seven, he went each night to hear Jain monks tell the Ramayana, the monks didn’t use any light, so he sat in darkness, for over 10 weeks, listening. ‘Dark is beautiful’ they said, ‘not to be burnt’. We have to shift our attitude of ownership of nature to relationship with nature. The moment you change from ownership to relationship, you create a sense of the sacred.” In the last week they've been so many mists, at first encircling the land like skirts at dawn and dusk, then becoming fog that stayed for two days. It was so encompassing that I could hear cars' music as they passed, but couldn't see their lights from the road 40 yards from my home, but if I looked straight up, I could still see stars 5.88 trillion miles away. My favourite thing to do on my pre-night pilgrimages, is to walk in the woods. At the moment, the only 'rains' that fall, fall in the woods. It is more like a temperate rainforest than primeval woodland: water droplets falling from the ivy, white stags in white mists swimming between trees, living stumps looking more like the broken pillars of Victorian cemeteries... Nobody started it, nobody is going to stop it. It will talk as long as it wants, this rain. As long as it talks I am going to listen." Last month, I only walked at the field edge alongside the spindle trees, field maples and field elms. Here, most of October was mating season, so it felt like trespassing to cross into their space. Instead, I listened to where the roars came from in the different rut stands. Now the shape and map of the woods in my mind is devided into the different stags' leks, not the human boundaries. As you walk between territories, you can smell them so strongly. Yesturday, a tree fell in the centre of the wood, uprooting two others with it and now all around them, there is a Glastonbury-level mud fest, where deer come to circle and eat fresh roots. With the fallen leaves and the cocktail-glass-shaped trooping funnel mushrooms knocked over, it's a bit like arriving a day late to what looked like an epic party. I have been researching fallow deer's history, learning about their first sea voyages, their first extinction on our island, the long associations of women and deer in art; the rare, Persian species Dama dama mesopotamica... but mostly I have been sitting in damp moss, as still as possible for as long as possible watching their slow movements as they walk past me; getting very cold, then returning home by moonlight, with gnome cheeks and dew in my hair. Empty and filled,

3 Comments

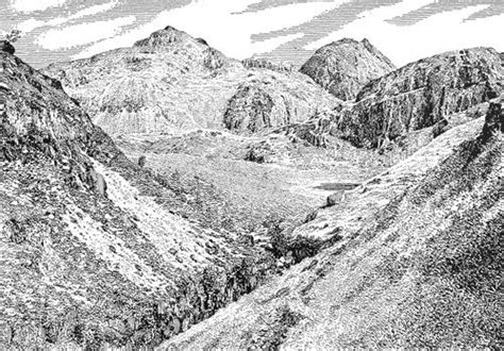

If the speed-walking naturalist, mountaineer, poet, author and diarist, Dorothy Wordsworth were alive now, I think she’d write for The Guardian; she might be Paul Evans or Alys Fowler, writing the Country Diary, or Gardening Column. Her writing would be credited, attributed, and published (probably by Granta or Canongate). Her collaborations would be akin to Edgelands, Weeds and Wildflowers, or The Lost Words. Herself, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William and Mary Wordsworth would co-create books like Holloway. Isabella Fenwick would have interviewed them, documenting their process, and, in a few years, Dora Wordsworth (daughter and niece), would publish essays on co-creating with nature, and the innovative, collaborative practises of her family. ‘The two best lines in it are by Mary’ There's was a pioneering way of composing, writing and editing poems, which if it had been more fully represented at the time, could have changed how we make and think about collectively making poems. In fact, if history had been a little different, and William Wordsworth, like Emily Dickinson had only published a handful of poems in his lifetime and the rest had stayed in a drawer in his bedroom, Dorothy Wordsworth would have been the more famous Jonas sibling and William, The Corrs brother. She would have been the Gilbert White of the Lake District, and had the fame and reprints of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. The sun had never once been overshadowed by a cloud during the whole of our progress from the centre of Borrowdale. On the summit of the Pike, which we gained after much toil, though witbout difficulty, there was not a breath of air to stir even the papers containing our refreshment, as they lay spread out upon a rock. The stillness seemed to be not of this world:- we paused, and kept silence to listen; and no sound could be heard: the Scawfell Cataracts were voiceless to us; and there was not an insect to hum in the air In terms of my poetic practise and the subjects I feel drawn to, one of the historical movements I feel most aligned with is English Romanticism. However, I feel a conflict, as a woman, it makes me feel tense; because I know how their collaborators, if female, have gone largely uncredited, and how still there is less attention given to understanding the psyche, influence and experiences of the women involved in this period. & at last under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of [daffodils] along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about & about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness & the rest tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing. This wind blew directly over the lake to them. There was here & there a little knot & a few stragglers a few yards higher up but they were so few as not to disturb… Most people can separate the humans from the work the humans make, especially if they’re long dead, but I find myself, for whatever reasons, struggling to do this. I can have a tendency to try to justify the actions of the time in terms of religious and societal pressures and norms, to make myself feel more at peace: however, when I compare the English Romantics to the American Transcendentalists of the same era, the Transcendentalists were setting up utopian, vegan farms, with equal pay for women and men; Margaret Fuller, one of the leading Transcendentalists was editor of the influential magazine, The Dial editing and deciding who did and didn’t get published; whilst Lord Byron, was ignoring the letters from one of his closest friends (Percy Bysshe Shelley) and Claire Clairmont (step-sister of Mary Shelley), the mother of Alba, his daughter; a daughter he later took away from her mother, renamed, and sent to a convent, aged five, where she died without any family present. When he received a letter informing him that she was ill, he did not go to visit her, or inform her mother. When I read personal histories with pieces missing, that champion certain Romantic poets as solitary geniuses, or depict key moments of their lives without showing the full psychological impact of everyone involved (and thus the reality of the emotional life for the main subject), they don’t feel truthful, or credible, or new. I would rather have the tension and relief of honesty: William Wordswoth was a brilliant poet, he both plagiarised and credited his sister for some of her work, perhaps he loved two women equally and simultaneously, he left one, Annette Vallon, to be a single mother. Lord Byron had the capacity for immense cruelty and regret, perhaps he was a true free spirit, or, perhaps he had an inability to commit. We are all imperfect, kind and cruel, awful and wonderful, giving and snatching, prejudiced and progressive, egotistical and thoughtful. ‘She gave me eyes, she gave me ears’ If the Romantics were alive today, I’m sure some of them would practise relationship anarchy, be poly-amorous, poly-curious, or in open relationships. Some might argue that they were practising “free love” long before the 1960s. Their version of free love though, was not weighted equally, it mostly benefited one person in each relationship, not two, or three, and certainly not the children of their relationships. It did not have the progressive, transformative qualities of some of their other beliefs. When polyamory is based on honest communication, love and mutual agreement; it’s beautiful, and can be empowering, liberating and healing for women. When it’s not, when it is lopsided and driven by one person, it’s not. Polyamory is about loving relationships, about caring for yourself, loving more than one person, and being equally loved, respected and cared for in return. In more recent, more liberal times, if the two women, Mary Hutchinson and Annette Vallon, and William Wordsworth had been poly, their lives would have been drastically different, but this was a time where to be married was to be legitimate, and to be illegitimate was to be abandoned.

There is a storm that just came in this evening, named Ciara. I am at The Wordsworth Trust for a month, in the Lake District, writing, walking and thinking about taking my tiny boat out. Today, I returned from doing a reading in London at a Poets for the Planet event, to launch the Extinction issue of Modern Poetry in Translation Magazine. I stepped down from the train (to change at Oxenholme), ran across the rain, and what I smelt was the sea. It is balletic rain. A corps of rain. I just got back to Grasmere, walked up the curving lane, where William and Dorothy Wordsworth would have walked, past Dove Cottage, and I smelt it again. It is ocean water that’s falling. We are an 8-hour walk from the sea, 23 miles inland, but I feel like I am by it, on it almost, with this North Atlantic storm, these winds bowling themselves down the valley. If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow: and without trees, we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either. So we can say that the cloud and the paper inter-are. William and Dorothy Wordsworth made their own ink. The rain that fell in Grasmere. A long, thick feather from a wintering bird. These were the things that went into their hands and writing. Dorothy made many of her notebooks: loose-leaved, stitched, minuscule, so they could be taken out and written in and on with pencil, on tours of Scotland, or walks where her lines slope, curve off and undulate as much as the hills and desire paths. Outdoors, there are no neat, straight, restrained lines. These are field notes wandering off like drunks at the end of the night; swerving, in motion, sometimes scattered across the page, slumped, slant and angled. The lines went where her eyes went: crags and fells and lake edges. If we look into this sheet of paper even more deeply, we can see the sunshine in it. If the sunshine is not there, the forest cannot grow. In fact nothing can grow. Even we cannot grow without sunshine. And so, we know that the sunshine is also in this sheet of paper. The paper and the sunshine inter-are. Sometimes, the pages would be taken out and shared between the collaborators (perhaps in their urgency to each be working on the same moment simultaneously): Dorothy, William, Samuel Taylor Coleridge - their thoughts and phrases configuring and resurfacing like water birds in each of their different works in each of their different rooms; merging and shifting and echoing each other in ways that are more akin to oral tellings and retellings of events. Dorothy would test the quill and ink by writing amen. On some of the pages there is a visual Tourette's of amens interrupting and exclaiming amen amen amen... The changes that happened to the texts were referred to not as redrafts and edits, but as alterations. The analogy is one of clothes, collage, quilting, of hemming and repurposing. When you look at the notebooks, they do feel like a collage, with rough zigzag repairs, darker ink words added above crossed-out words, stubs where pages have been cut out, pastedowns and new paper flaps added for edits, Dorothy's writing next to Mary's next to William's next to notes added perhaps a hundred years later in pencil by their relatives. The manuscripts I held in my hands this week, are 50 yards from where they were first written 200 years ago, these notebooks were once cloth, rags, bleached and made into paper which still carry a tint of the old colour when held up to sunlight. The pages were worn once here in this place, a piece of The Prelude, a journal entry on shoulder or sleeve or newborn or shin, which in turn was once linen, which in turn was once flax plants, spun from the long fibers which grow just beyound the bark of the stems. The storm is now powerhosing the front of the house. It is late and I am wondering if they ever had rain like this: ink salt water, the affair-like scent of somewhere else entering their house. And if we continue to look we can see the logger who cut the tree and brought it to the mill to be transformed into paper. And we see the wheat. We know that the logger cannot exist without his daily bread, and therefore the wheat that became his bread is also in this sheet of paper. And the logger's father and mother are in it too. When we look in this way we see that without all of these things, this sheet of paper cannot exist. With immense appreciation and gratitude to Jeff Cowton, Curator and Head of Learning at The Wordsworth Trust: for exquisite ideas, inspiration, generosity, brilliant questions, time, and for showing and sharing the manuscripts with me, as well as Dorothy Wordsworth's pockets, on my first week in residence.

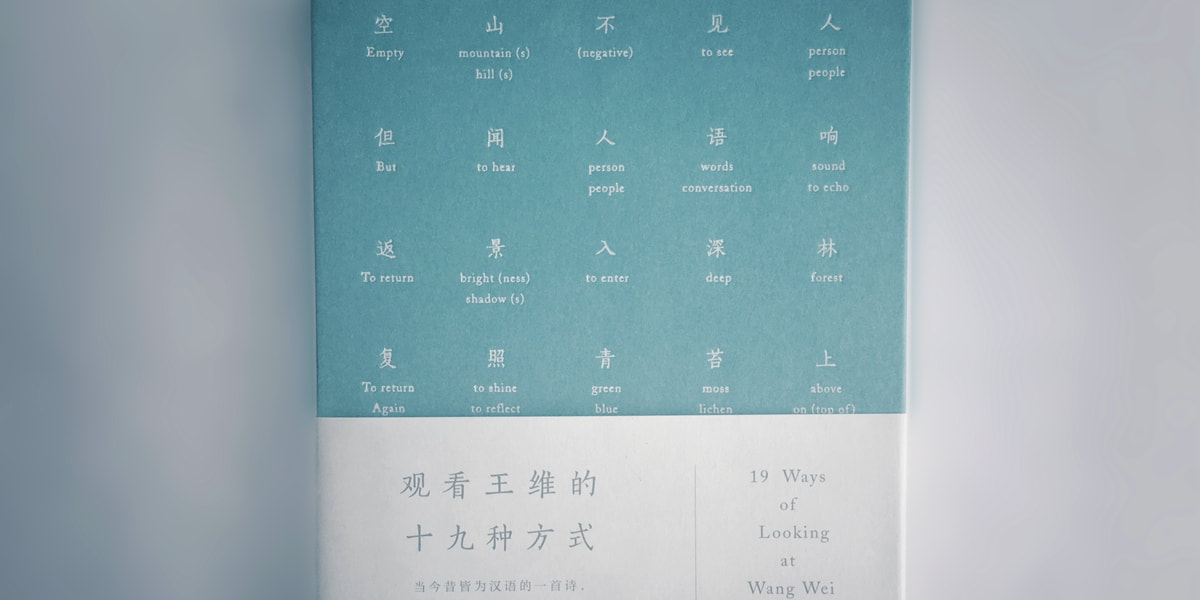

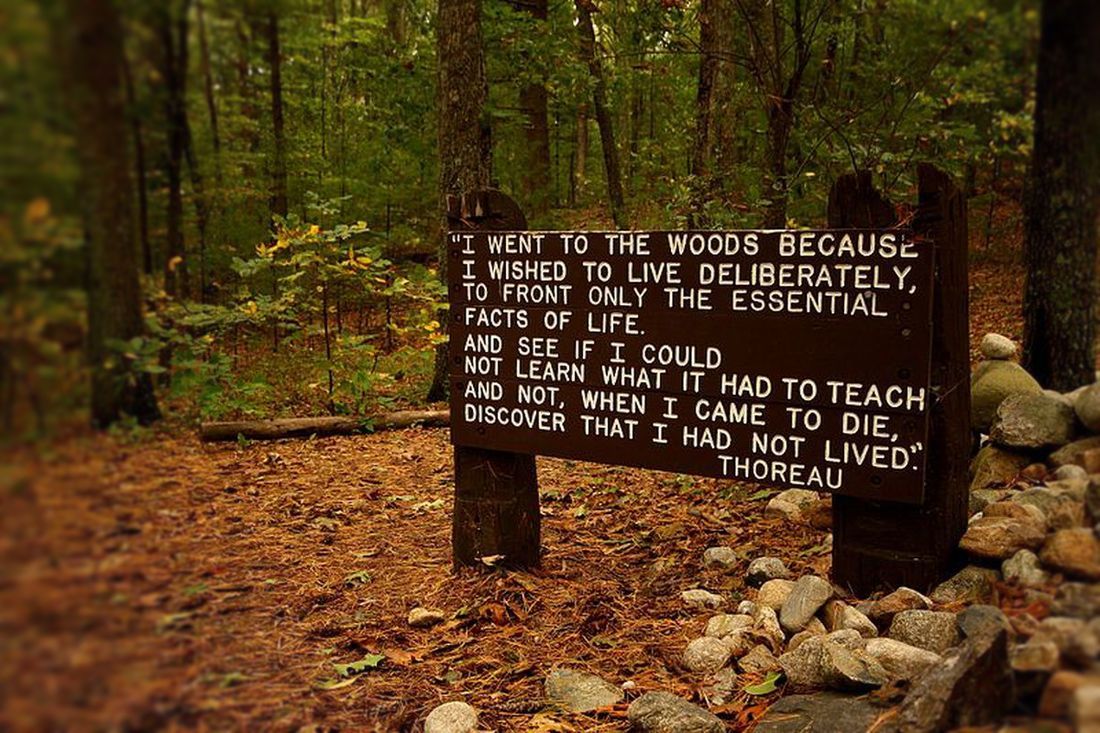

When you’ve lived in a city for so many years, darkness becomes a luxury. Last week, I was volunteering with an off-grid, Eco-community called Brithdir Mawr. One night, I stepped out from the farm house into the stars. The darkness was so complete, I couldn’t see where feet, stream or ground were. When I returned an hour later, all was bright again, the moon had risen with its amber hum around it. The first few nights had been the nights of The Full Snow Moon - the biggest and brightest supermoon we’ll have this year. Leaving the outdoor bathroom was like opening a door and walking back into daylight: everything lit-up, my moon shadow in front of me on the way there and behind me on the way back to my cottage. Those nights were hard to sleep through. On my second night, I’d sat up listening to a male tawny owl calling and calling without answer. I’d got so used to not needing a head-torch, that I’d packed it away again. It reminded me of trying to sleep whilst camping in Iceland in June, with 24 hours of daylight, when the sun had teased us by lowering towards the sea only to curve right back up again. Nights like these make me think of a night-gardener I once stayed with, he would look after his young children throughout the day, bathe and sing them into bed, then be out in the garden with his head-torch. Every time he glanced up, the light would transect my window. I wonder what sounds he heard and creatures he saw. Night gardens have different shifts and rotas, bats are the first to swing out, frogs surface and gather at the edges of ponds, toads lumber across the paths, barn owls float over… It is my dream one day to plant and make a walled moon garden, not the bright, crayon flowers that are for daytime moths, bees and butterflies, but pale starlets, ghostly, perfumed night-flowers for bats, nocturnal moths and night-flying insects; jasmine, moonflower vines, gardenia, evening primrose, datura, brugmansia (which opens for a week with the full moon), Japanese wisteria, tuberrose, night phlox and nicotiana (a flowering tobacco which opens at dusk). Selenicereus grandiflorus, known as The Night Blowing Cereus or Queen of the Night, is a cactus that blossoms once a year, for only one night. Its flowers are one-foot in diameter, often opening in the early evening, reaching peak bloom by midnight. Its scent is similar to vanilla. The gardens at Brithdir are fringed with snowdrops, catkins, primroses, daffodils, narcissus. Whenever a breeze turned I’d catch the scent of spring flowers or coconut from the gorse bushes. The earth is so fertile that tall mint grows from puddles on the tracks and wild celery in the boggy marshland between polytunnels. The outdoor work of coppicing, mulching, preparing firewood, weeding, milking, planting, digging, cutting, chopping, feeding, harvesting, sawing and fencing is demanding, but it stops in the afternoon before dark, whilst in cities and towns we go on through these dark, colder months in exactly the same way as we go on through the bright, hotter ones. Emma Orbach, who co-founded Brithdir community and has lived just down from it for the last 20 years, described the irrationality of this when we went down to visit her, how people work through these lethargic months as if nothing is different. The name of the farm, Brithdir Mawr means ‘Great Speckled Land’. It was shaped by the last glacial period. Everywhere you dig the earth offers something different, clay in one spot, a few meters to the left, gravel… If you look in one direction you look back at the Preseli Mountains and if you turn around you look out to the pembrokeshire coast and sea. The winds were keen and the sun had come to wake everything up while I was there. One of last year’s butterflies, a red admiral, fluttered into the kitchen one afternoon. There were bees and wasps, a fox moth caterpillar on the way up Mynydd Carningli (Mountain of Angels), apricot and blackthorn blossom and the wild garlic leaves were already ready to be picked along the drive. Winter lettuces, spring onions, parsley and physalis were growing in the polytunnels and glass houses, the soil was full of winter vegetables, the scullery shelves lined with jars of last year’s produce: passata made with ‘Gardeners Ecstasy’ tomatoes (a sweeter hybrid of 'Gardeners Delight', bred by resident Tony Haig), Blackcurrant and Birch Sap Wine, chilli sauce, chutneys, jams, syrups, ketchup, stewed apples, plaits of garlic and onions hung from the ceilings and sacks of potatoes piled up around our feet. Sometimes when we think of living off grid in sustainable, self-sufficient communities, we think of what we’ll lose or have to give up, rather than all the things we gain: to be able to work less and do more of what we love, due to a reasonable, seasonal, shared way of living; to be healthier, stronger, more attuned; to shower in steaming hot spring water; to be greeted by the smell of freshly baked bread most lunch times and have every evening as a dinner party, or film nights, or games nights, or music nights; or just to browse a library made by people over 20 years and sit by yourself reading in a sunbeam with a cat in your lap; to be cooked for every night, to cook for others; to share child care; to be ourselves and get your sense of identity back as new parents; to see your children embrace their right to be alone in nature and run further from you than they ever have in their lives; to be able to afford fresh, organic food because you grow it outside your window; to laugh at jokes so terrible they’re wonderful; to listen to singers you’ve never heard before but are smitten by; to share your lives and life stories before the first coffee of the day; to look after each other and our lovely planet; and to sit in an armchair (built from the ash trees you see from your bedroom window), talking to the man who designed and crafted it, watching a fire you made catch, as the wind pulls it up into the chimney. When I’d first arrived in the nearest town, I’d been absorbed by a wonderful family who run a local hotel, then met a dog-walker beside the estuary. She’d lived in the area for 26 years. She said the same word always comes to her for this landscape: hiraeth. For her, it meant calm, peace. Hiraeth is a Cymraeg (Welsh) word, concept and feeling. It doesn’t have an equivalent in English. Some people translate it as a sense of yearning for a place or way of life you know you’re meant to be living. It contains both a pull and gratitude. One attempt to describe it, says it’s “a longing to be where your spirit lives.” Brithdir Mawr is a very rare place, and a bighearted, hardworking, incredibly knowledgeable group of people. No chemicals are used anywhere, all the produce is grown in intuitive and natural ways and is organic, they generate all their electricity from wind, water and solar power, firewood is cut from a seven-year rotating coppice planted and tended by the people who live, work and volunteer there: water is heated by fires and everyone lives with as little impact as possible on the environment and land. Currently, there is an opportunity to support Brithdir Mawr, to enable it to be held in a Trust, to sustain, share and expand their methods, and a more realistic, considerate and affordable way of living for ourselves and future generations. The community also welcomes volunteers once a month, has space for new families, couples and individuals to join, and has camping and glamping available each summer. When calves sleep, they sleep like they’ve spilt. I’ve spent years watching them, waking with them sneezing outside my front door, sitting next to them under the only tree to offer shelter in a hailstorm, seeing their rodeo play. The herd and calves I got to know this summer were nomadic, walking from the mountain, through the fallen stonewalls between fields, right to the edge of the ocean. They tore up the short grass as if it was on bone. There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery Today, I have been wondering about the poets with soil under their fingernails. Not just those who farmed, but those who grew and tended and worked with the land, who had a living calender. Henry David Thoreau planted two bean crops near Walden pond during the two years he lived there, he also advised locals on which native trees to plant and claimed he could tell the time of day by which flowers were open. Emily Dickinson, not content with the lack of practical clothing for women designed and made her own ‘house dress’ so she could garden and study botany outdoors. One farmer says to me, 'You cannot live on vegetable food solely, for it furnishes nothing to make bones with; and so he religiously devotes a part of his day to supplying his system with the raw material of bones; walking all the while he talks behind his oxen, which, with vegetable-made bones, jerk him and his lumbering plow along in spite of every obstacle. I went to find Thoreau’s bean field once. It was surprisingly small: what would have been a few rows which are now in the deep shade of a deciduous wood. A Shropshire poet called Marilyn Gunn wrote almost all her poems in the greenhouse of her allotment, and contemporary poet Richard Osmond is a professional forager, whose written about his searches for winter chanterelle mushrooms and the right tint of green among all the greens. The world and our life in it are conditional gifts. We have the world to live in, and the use of it to live from, on the condition that we will take good care of it. And to take good care of it we have to know it and we have to know how to take care of it. And to know, and to be willing to take care of it, we have to love it. And we’ve ignored all that. When Wendell Berry, was asked at an event what connected his art with his farming he replied, that farming like poetry, is an art. And that he does the best he can to connect the two, all the time. Historically, many farming poets were self-taught. Irish poet and farmer Patrick Kavanagh would walk to the library in the evenings to read poetry, Kurdish poet, Bejan Matur grew up on a farm and would sit up a tree as a child to escape her duties and read the classics. There is a long line of poets who grew up on, or in farming families: ancient Roman poet, Virgil; Zimbawean poet, Togara Muzanenhamo; Chinese poet, Yu Xiuhua; Australian poets Les Murray and John Kinsella, and here in Ireland Seamus Heaney (whose father was a cattle-dealer and farmer) and Bernard O'Donoghue. Then there are those who chose farming: Robert Frost, Robert Burns, Tess Taylor, Ted Hughes, and those who worked as agricultural labourers, the most famous of which is John Clare. I found my poems in the fields In 1840, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, George Ripley stood up in front of the Transcendentalist Club and voiced an idea he’d had. By the next year it was a reality and the first farm based on the ideals of Transcendentalism was established. It was named Brook Farm and was a community of like-minded women and men who shared the labour collectively, were paid equally and shared the profits. The vision behind it was that this would give them more free time to pursue intellectual ideas and leisure activities. Fruitlands was the second farm, set up two years later by the Transcendentalist, Amos Bronson Alcott. It was a completely vegan farm, using no animal labour and no animal products (including no wool, beeswax for candles or whale oil for lamps). Both were visionary projects, full of hope and gusto. Ripley believed his experiment would be a model for the rest of society. He predicted: "If wisely executed, it will be a light over this country and this age. If not the sunrise, it will be the morning star.” The Man Born to Farming Before I was born, my parents lived off-grid. They had a small holding in Ireland which they shared with my Uncle and his partner. They grew almost everything they ate, harvested peat from the moor for the fire, lit paraffin lamps for light, went everywhere on horse and cart and built a runnel to get water down from the lake. My eldest brother Jesse, who was just a baby at the time learned to walk on those runnels. It was a time of abundant crocheting, with my Dad being the most abundant. This is evident in their wedding pictures in which the hats and buttonholes are all crocheted. The only things they bought were oats, rice, wool and paraffin, which they financed by making and selling crocheted fairies. I am in Ireland at the moment, not far from where they lived, looking up at one of the black, hectic skies they always described, and when they described it, they talked of shock, tiredness, love. Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota Yesterday, I saw one of the first salmon running. They remind me so much of the moment a plane levels off over the clouds. It came out of the water like an idea. That leap. I walked upstream and imagined it swimming beside me, past the jazz-like calls of coots and moorhens, under the leaves and weeds floating against it. I often keep watch for the first heavy rains in late summer and early autumn. I know that when these rains come, they’ll come - gathering at the foot of cliffs and mouths of estuaries. This is one of their signals to head home, to migrate. I watched them once, at dusk, on television, run, Atlantic Salmon are sea fish and Atlantic Salmon are freshwater fish. The scientific name for them is their prophecy, Salmo salar: salar, meaning to leap (from the Latin, salio) - and one of the terms used to describe them means, running upward, or up course (anadromous). They are born inland, they morph in the brackish border between saltwater and river, travel far out into the deep ocean, then, when they are about five, they return to the exact place they were created, to create new life. No one understands fully how they know how do this. They eat nothing on their trip back. They can jump up to 12 feet. Some have to travel almost 1,000 miles and climb 7,000 feet. In this shallow creek It is one of the greatest rituals of the year, to come and witness their migration. It is a tense drama though. A tragedy. I often wonder if it is the weaker swimmers I’m seeing attempting, then attempting again and again to jump the weir. There is a paparazzi of cameras pointed at them. An intensity of people trying to get a spot with their tripods. A warden keeping the number of photographers down and back. Once the fish have spawned upriver, many never make it back. Living In 1853, it was a perfect autumn. During the month of October, 165 years ago, the nature writer, Henry David Thoreau took Ralph Waldo Emerson’s children, his friends and family barberrying by boat, sailing at Fairhaven Bay and paddling on the Assonet and Concord river. While doing so, he constantly made notes in his journal about leaves. They astounded him that year, in a way they’d never done before. Each year, I make a pilgrimage to a different writer's house. In 2016, it was Thoreau’s home: Walden. I walked the route that Emerson and Thoreau used to walk together. I didn’t realise it at the time, but I walked one of Thoreau’s essays that day. It was my first Fall in New England. It was psychedelic, technicolour, inconceivable. I went around as if high: gawping and in awe. It was an Indian summer. I arrived on the date Thoreau’s essay began. The time of year, the weather, everything was identical to Autumnal Tints. I walked down aisles of leaves, a bird of prey followed me from Emerson’s house out along the streams and marshes moving from tree to tree. With each curve in the path, I had to stop to stare at a new sight of a tree. It was as if I were a bridegroom turning and it the bride. It was a huge American Elm that made me realise what Robert Frost meant by his yellow wood in The Road Not Taken. I grew up with a cherry blossom tree outside my bedroom window. As a child, I called it a blessing when you stood underneath and shook the branches, or walked under falling leaves. That’s what this mass death of leaves felt like to me: celebratory - a wedding, a carnival, ticker tape, confetti. How beautifully they go to their graves! How gently lay themselves down and turn to mould! They stoop to rise, to mount higher in coming years. The year’s great crop. They teach us how to die.’ Kintsugi, or Kintsukuroi is the centuries-old Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics with gold, silver or platinum. The scars and seams are not hidden, but visible: a golden root system. Somehow the object becomes more valued, more artful than it was before it fell. This is what fish do: they solder their own wounds shut with a silverish joinery. The first time I discovered this, I was swimming in the centre of a shoal of schooling Axillary Seabream, Pagellus acarne. Either I was herding them, or they were choreographing me. It wasn’t clear. I moved in their hundreds. Right in the centre of this thicket, was an injured fish. It was like seeing a semi-precious stone. The mending of silver caught the light - it shone more than the other fish, it looked like an abstract sculpture, with a crescent of its body missing from a large fish or seabird bite. Unlike birds, fishes’ appearance don't differ so much between males and females, so schooling fish have a slight cloned affect. It looks very military, very shepherded, very surreal. The more you study them and return to the same place, the more you notice their differences. The school I was swimming with were quite young and mostly all male. Gender roles are not so binary as they are in our species and many fish change sex, or are hermaphrodites. Like gulls, some fishes’ characteristics change as they age and you can ‘date’ them by these changes. For others, their size and shape indicates when they swap genders. One of the most dramatic transformations is that of Wrasse. They have a kind of light bulb moment, but the light bulb grows in the top of their head. They look partially inflated. Clownfish have a matriarchal system; when the top female dies, the most dominant male becomes a female in her place. Fish are some of the trickiest things to identify; their size is distorted by the water, as is their colour depending on light, threat, depth, weather, time of day, age. When you’re learning to identify marine species and you do a search online, the images that come back are almost always of a hanging: their bodies held up, in a man’s arms, laid in ice, or on a plate. I had not anticipated this. I expected them to be alive and in water. It is as strange to me as it would be if all the images of Blackbirds, Robins and Goldfinches, were not of them in flight, or perched, but fried and bald, or swinging upside down with their beaks pierced. The words that comes up again and again, are not species, habitat, ecology; but game, restaurant, aquarium. The colours of fish underwater are extraordinary, especially turquoise. Many fish have a current of electric, azure blue roped and zig-zagged around them. A new visitor to our waters is the Grey Triggerfish, Balistes capriscus. I got a close look at one earlier this summer when it tried one of my toes. It has a wonderful blue pointillist pattern. Nothing is ever the same when you go underwater: one day all the crabs will be circumnavigating a buffet of rocks, the next starfish are splayed like drunk party guests; then the day after that, there is an underwater smog, so thick you can’t see anything. My most unusual experience, was the day thousands of small salp-like organisms were near the shore, floating around me like hollow planets. I am still trying to solve what they were. I think the poets that often come to mind when I’m swimming in the sea, or studying fish are Ted Hughes, Elizabeth Bishop, Stephanie Norgate and H.D. And for abundance - for all their plurals and collective nouns, this poem, by Galway Kinnell. Daybreak After three months of wandering, I returned to a different season last week. I still feel like I am not here. A few years ago, Aviva Dautch, a friend and poet, told me the saying: the soul travels on horseback. I am still galloping. Still en route. The bougainvillea of building sites have been replaced with buddleia; pepper trees’ berries are now Rowan bayas, and the perpetual spring of Tenerife, is aging. No, no matter your thirst, ride swiftly, mare, stallion, I have stowaways on the laces of my trainers from the highlands: mountain seeds. They’re like burrs, and are so good at doing their job that they even stick to your skin. The last time I was in Dublin - while my cooler friends, Vicky and Gemma got matching tattoos in Temple Bar, I went to Dublin Writers Museum. I read about a poet who put mud on the soles of his boots when he came into the city, to remind city dwellers of the turf beyond their streets. I will arise and go now, for always night and day William Butler Yeats’ poem The Lake Isle of Innisfree was written in 1888 whilst he was living in London, missing Sligo. I thought of the poem often when I lived there, and when I was living up in my mountain hut in Ireland. Although Yeats lived in Dublin, he'd spent many of his childhood summers in Sligo. It was as he was walking along Fleet Street that he had the memory of an uninhabited islet in Lough Gill, heard the lake and then the poem. To listen to the quiver of him reading it is one of life's joys. I had still the ambition, formed in Sligo in my teens, of living in imitation of Thoreau on Innisfree, a little island in Lough Gill, and when walking through Fleet Street very homesick I heard a little tinkle of water and saw a fountain in a shop-window which balanced a little ball upon its jet, and began to remember lake water. From the sudden remembrance came my poem "Innisfree," my first lyric with anything in its rhythm of my own music. I had begun to loosen rhythm as an escape from rhetoric and from that emotion of the crowd that rhetoric brings, but I only understood vaguely and occasionally that I must for my special purpose use nothing but the common syntax." There was a period in London when I was working extremely long hours for several months and living in a very built-up area. One commute, I noticed something different about the man standing in front of me on the escalator, but hadn’t registered what. He was a suited man with beetle-black polished shoes. On his heel was a bright, wet, green clump: mown grass. It was the only way I knew the seasons were changing. It had been an endless winter. I had been rushing to work in the dark, and returning in the dark. Each day was a repeated stitch: wake, bus, tube, work, tube, bus, sleep. My route was all cement, brick. That morning, imagining him hurrying across his dewy lawn, I realised I’d taken my thread too deep into the maze of the city. I’d lost my elements. Since then, I have tried to live in every season, inhabit them, breath and note and taste them, dive into cold water most days, eat outdoors, run through parks, or mudlark on my lunch breaks along the Thames foreshore… I wish men would get back their balance among the elements It has been a long, burning summer. Now I am back. I am not feeling homesick for one place, but for people, for being on the move, meeting and visiting friends and family. I leave little bits of my heart scattered. It is as damp as monsoon season here. I am sat listening to the weather and watching the direction of the wind. Without trees we cannot hear the subtler breezes. I have been without the mosh and sway of long grasses, branches - willow, ash, lime, oak leaves. I have missed how alive it makes you feel to watch them.

When you don’t speak a language, you hear how things are said, the energy in a conversation, and notice when people choose to say nothing. This weekend, I climbed Spain’s highest mountain: Mount Teide. I did it with a group of native Spanish speakers from the Canary Islands, Latin America and mainland Spain. As we hiked up the mountain - the patterns, and regularity of certain words changed. When we began: “vamos”; when we walked into the shadow of the mountain it was “frío”; each time we stopped and turned around “bonita”; as we walked out in total darkness at 5am: silence, no one spoke; as we ascended “silueta”, as we reached the crater at dawn and saw the world’s longest shadow stretching over the Atlantic: “la sombra”. A few years ago, I went to FLUPP festival in a favela in Rio and remember noticing how people's conversations felt like they had a temperature: they seemed to bubble and ping and were so full of gusto and vim, compared with the flatness of my own language (where people speak to each other as if they’re not fully awake yet). I love this about languages like Spanish, Portuguese and Italian: how they take off. Everything sounds caffeinated. I feel so tethered, compared to exclamations of ‘a’s and ‘o’s and the rolling engine of ‘r’s. Earlier this year, a poem had risen up in me, dream-like, about Teide Violets - a flower that pretty much only grows on this volcano, on the island of Tenerife, at a specific altitude. It is a small and massive poem to me: about how maternally protective I feel, and heartbroken by the loss and vulnerability of certain species. The poem will be published in the forthcoming Climate Change issue of Magma magazine. In the poem, I walk up the volcano through the night, guided by a man I don’t know. In the Mountain refuge on Saturday evening, a wonderful Venezuelan woman, Aliee, that my friend and I’d met, said: “This is not chance. I have been looking for you.” The whole experience had this feel to me. I found myself living the poem that had come to me three months earlier. I had not planned to climb the mountain, definitely not with a male guide, and had no idea that when you climb Teide, this is how you do it: in the night, in blackness - such blackness that you can’t even see the silhouette of the mountain, where it stops and where the night sky begins. You walk up into galaxies and shooting stars and the smear of the milky way. We were a group of about 20. When I looked up or down and saw the trail and clusters of headlamps along the path I thought we looked like our own constellations. My mother used to say to me as a child that I was made from stardust and this journey felt like us returning ourselves to the heavens. When I re-read Johanna Spyri’s children’s book Heidi this summer, the mountain felt like one of the main characters. So much of the narrative centres on them climbing up and down it like a ladder. Mount Teide felt like our plot. We walked into it. We crossed into its shadow with such relief to finally be out of sun and heat, then turned from it when we reached the Altavista Refuge only to see its sombra across the earth's atmosphere, with Gran Canaria next to it seeming to grow out of clouds. On a clear day you can see every one of the canary islands from Mount Teide and you can see Mount Teide from every one of the islands. Its shadow is so vast, that it is like watching an eclipse. It has a halo around its crater, and drapes like cloth over the surrounding mountain range, ocean and islands. The higher you get up the mountain, the harder it is to make out what is sea and what is sky, unless there are boats; and as you ascend, it becomes impossible to look at anything but where your feet are. There are vents and cracks which your sticks get jammed in, plus a fallen empire of rubble, loose rocks and scree to slip and turn your ankle on. Last year, I went to Iceland. As the plane flew in, I thought the landscape looked traumatised. Teide National Park is the same: an outburst, made by fire and heat, wounded. The earth is black and red and brown - broken and cut and coughed up and turned and spilled. It looks like chaos. There has been no water here to sooth it, as there was in the landscapes I grew up in, that were softened and made slowly by water, carrying and holding the memory of it in their undulations and cupped hands. The making of this place feels abrupt, violent. I can’t say if I felt happy in it. An English poet called Helen Mort has written a brilliant collection about female mountaineers and mountaineering, No Map Could Show Them. As part of the research she hiked in crinoline skirts and petticoats to recreate what some women would have worn. In my group, on the first day, a phenomenal woman, Rossi, climbed the mountain in hotpants, a Glee-style crop top and sideways basketball cap. She was the sun of our group - even in the darkness and tiredness of the second day. She lead at the front for much of the hike, would Facetime her brother, Ivan, at various altitudes (and we’d all wave back at him in his warm house), she sang to us to keep our energy up, had us laughing and taking selfies at every stage, and got a collection together to tip the bus driver on the way back. Another man played R&B very loudly for two hours from his phone, dancing and skipping around each curve of the track, at the rest stops some people would light up and many people chatted on their mobiles as they hiked up until the signal was lost. I loved the lack of reverence and conformity. I had not pictured myself mountaineering with Despacito as my backing track. It felt freeing and unBritish. It reminded me of when I’d go skiing, listening to Bollywood and hip-hop all the way down the slopes. Two of my favourite international poets are mountain women: Bejan Matur and Kutti Revathi. Bejan is a Kurdish poet who was born and brought up on a farm in the mountains of north Turkey. Mountains are so present in her work that even though she left many years ago, they still live in her. The more you confine me, Kutti is a Tamil poet who lives and has the courage of someone who has grown up overcoming the difficulties of height and distance. She lives in mountainous Tamil Nadu in India, runs a feminist literary magazine and explores the landscape and reclaiming of the female body. The first poem I read of hers is called Mulaigal, Breasts and was translated by the late Lakshmi Holmström in the anthology Wild Girls Wicked Words. BREASTS One of the most beautiful books written about how mountains inhabit you, is Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain. When I go to watch the deer rutting each autumn in Richmond Park and hear their bellows and horns interlocking (which sound just like the crunch of American football players), I think of her descriptions of the stags jousting to the death in the Cairngorms. There is something that brings us to mountains. Sometimes as healing places, as in Susan Trott's Holy Man trilogy, sometimes as safe spaces, as our ancestors did in the previous ice ages and on migratory routes, and sometimes to prove to ourselves that we can be where we weren’t made to be: where we can walk at the bottom of the ocean floor and step in and out of clouds.

There are as many blues underwater as there are greens above. You don’t notice it when you’re down there. But afterwards, when you’re looking through photos or videos, it’s the first thing you see: Ink, Bombay Sapphire, Glacial - and you a dark putto, hovering in a sky. You can feel a bit like an icon under there with the sunbeam halos, glories and water-spectres. I've been doing a diving course over the last few weeks. Each time our instructors wanted to teach us something, they would gather us on the seafloor in a circle, or facing them, and show, or sign to us what we needed to know and do next. I’ve learned many lessons in my underwater school: to navigate by the direction of sand ripples, or the angle of the sun; that I can make myself the weight of water, and when I weigh what water weighs, I need do nothing but lay on my tummy, gravity-less, an astronaut being swashed around a little by the tides; I’ve watched how teachers' and students' breaths become alchemy: lava-lamp like, mercury streams that merge with one anothers’, and are pulled aside like a stage curtain. One of the things I was most nervous about, was one of the the things I enjoyed most. For one exercise, I had to release my air and turn it into a furious torrent - a kind of upside down waterfall which I then sipped from with the corner of my mouth. In Spanish, the word for waterfall is cascada. It was this, but the wrong way round, in this jaunty world where the ceiling seems to be the floor. The thing that blew me away, was that it tasted sweet, and that I was in water, ‘sipping’ air like a kitten. After each dive my mouth would feel a little puckered - as if I’d been blowing balloons up for too long. I was silenced by the water - exhausted, and very still, very quiet. Each night, when I lay down, I had dock rock and would be swaying and lifted in a phantom choreography. On our second dive, I missed the surface - I had culture shock: a homesickness and longing for the familiar comfort of breezes, noise, voices. When you dive, red is the first colour you lose. Then orange. Yellow follows. Green. Blue. And finally, violet. You can measure and know how deep you are by their loss. The depths of the sea carry the same names as dawn and dusk and night: twilight, midnight, sunlight zone. A deep-sea diver told me that one time, she was surrounded by so much blue that the only way she knew which way was up, was by watching her air bubbles. I often think of this descent as a breaking up and dismantling of the rainbow, until only a celestial black space is left - it reminds me of a poem called The Darker Sooner by Catherine Wing. Then came the darker sooner, In Richard Dawkins’ book about the partnership of art and science, Unweaving the Rainbow, he opens with a reference to John Keats. Once, when everyone had sat down for a dinner, Keats raised his glass and proposed a toast "to the confusion of Newton". When his friend (and fellow Romantic) William Wordsworth paused before drinking, and asked what he meant, Keats replied: "Because he destroyed the poetry of the rainbow by reducing it to a prism." Do not all charms fly The sciences used to be called Natural Philosophy; and Scientists - Natural Philosophers, thinkers, questioners - wondering and imagining. I have found nothing unpoetic in science and have no less awe for trying to understand things to a molecular or chemical level. In fact, I see more of a kinship between poets and scientists than I do other artforms sometimes: both are diligent observers, both trying to capture, understand and convey something honestly. Both are wonderers. There are many young poets working in this way: Marshallese poet and climate change activist, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner - and in the UK: Dom Bury, Isabel Galleymore, Karen McCarthy Woolf, Jen Hadfiled and Nancy Campbell to mention only a few. Science is poetic, ought to be poetic, has much to learn from poets and should press good poetic imagery and metaphor into its inspirational service." It has only been a day since I finished the course and already I am missing being underwater. For me, the best classrooms are not rooms and the best lessons - not just factual, but felt: what it feels like to look a sea turtle in the eye, so close you see yourself reflected in its iris - and then to have this ancient creature, (whose species is 150-million years old) swim vertically up over your body; how it feels to always have someone beside you and you both looking out for each other (most of SCUBA teaching focuses on how to save, calm and keep each other safe); what it’s like when a species of fish you haven’t seen before drips down in front of you unexpectedly; and most of all, what it is to be in a border-less space that connects every part of our planet. You feel, truly, part rather than apart, as if you could go everywhere.

|

Author

Anna Selby is a naturalist and poet. Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed