|

If the speed-walking naturalist, mountaineer, poet, author and diarist, Dorothy Wordsworth were alive now, I think she’d write for The Guardian; she might be Paul Evans or Alys Fowler, writing the Country Diary, or Gardening Column. Her writing would be credited, attributed, and published (probably by Granta or Canongate). Her collaborations would be akin to Edgelands, Weeds and Wildflowers, or The Lost Words. Herself, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William and Mary Wordsworth would co-create books like Holloway. Isabella Fenwick would have interviewed them, documenting their process, and, in a few years, Dora Wordsworth (daughter and niece), would publish essays on co-creating with nature, and the innovative, collaborative practises of her family. ‘The two best lines in it are by Mary’ There's was a pioneering way of composing, writing and editing poems, which if it had been more fully represented at the time, could have changed how we make and think about collectively making poems. In fact, if history had been a little different, and William Wordsworth, like Emily Dickinson had only published a handful of poems in his lifetime and the rest had stayed in a drawer in his bedroom, Dorothy Wordsworth would have been the more famous Jonas sibling and William, The Corrs brother. She would have been the Gilbert White of the Lake District, and had the fame and reprints of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. The sun had never once been overshadowed by a cloud during the whole of our progress from the centre of Borrowdale. On the summit of the Pike, which we gained after much toil, though witbout difficulty, there was not a breath of air to stir even the papers containing our refreshment, as they lay spread out upon a rock. The stillness seemed to be not of this world:- we paused, and kept silence to listen; and no sound could be heard: the Scawfell Cataracts were voiceless to us; and there was not an insect to hum in the air In terms of my poetic practise and the subjects I feel drawn to, one of the historical movements I feel most aligned with is English Romanticism. However, I feel a conflict, as a woman, it makes me feel tense; because I know how their collaborators, if female, have gone largely uncredited, and how still there is less attention given to understanding the psyche, influence and experiences of the women involved in this period. & at last under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of [daffodils] along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about & about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness & the rest tossed & reeled & danced & seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing. This wind blew directly over the lake to them. There was here & there a little knot & a few stragglers a few yards higher up but they were so few as not to disturb… Most people can separate the humans from the work the humans make, especially if they’re long dead, but I find myself, for whatever reasons, struggling to do this. I can have a tendency to try to justify the actions of the time in terms of religious and societal pressures and norms, to make myself feel more at peace: however, when I compare the English Romantics to the American Transcendentalists of the same era, the Transcendentalists were setting up utopian, vegan farms, with equal pay for women and men; Margaret Fuller, one of the leading Transcendentalists was editor of the influential magazine, The Dial editing and deciding who did and didn’t get published; whilst Lord Byron, was ignoring the letters from one of his closest friends (Percy Bysshe Shelley) and Claire Clairmont (step-sister of Mary Shelley), the mother of Alba, his daughter; a daughter he later took away from her mother, renamed, and sent to a convent, aged five, where she died without any family present. When he received a letter informing him that she was ill, he did not go to visit her, or inform her mother. When I read personal histories with pieces missing, that champion certain Romantic poets as solitary geniuses, or depict key moments of their lives without showing the full psychological impact of everyone involved (and thus the reality of the emotional life for the main subject), they don’t feel truthful, or credible, or new. I would rather have the tension and relief of honesty: William Wordswoth was a brilliant poet, he both plagiarised and credited his sister for some of her work, perhaps he loved two women equally and simultaneously, he left one, Annette Vallon, to be a single mother. Lord Byron had the capacity for immense cruelty and regret, perhaps he was a true free spirit, or, perhaps he had an inability to commit. We are all imperfect, kind and cruel, awful and wonderful, giving and snatching, prejudiced and progressive, egotistical and thoughtful. ‘She gave me eyes, she gave me ears’ If the Romantics were alive today, I’m sure some of them would practise relationship anarchy, be poly-amorous, poly-curious, or in open relationships. Some might argue that they were practising “free love” long before the 1960s. Their version of free love though, was not weighted equally, it mostly benefited one person in each relationship, not two, or three, and certainly not the children of their relationships. It did not have the progressive, transformative qualities of some of their other beliefs. When polyamory is based on honest communication, love and mutual agreement; it’s beautiful, and can be empowering, liberating and healing for women. When it’s not, when it is lopsided and driven by one person, it’s not. Polyamory is about loving relationships, about caring for yourself, loving more than one person, and being equally loved, respected and cared for in return. In more recent, more liberal times, if the two women, Mary Hutchinson and Annette Vallon, and William Wordsworth had been poly, their lives would have been drastically different, but this was a time where to be married was to be legitimate, and to be illegitimate was to be abandoned.

4 Comments

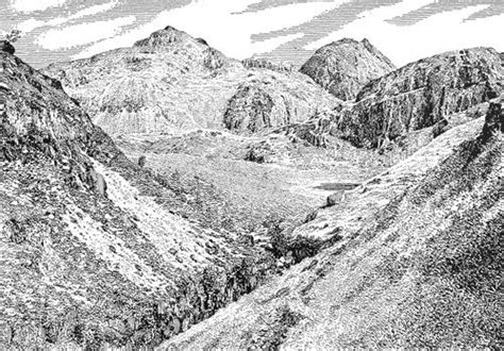

There is a storm that just came in this evening, named Ciara. I am at The Wordsworth Trust for a month, in the Lake District, writing, walking and thinking about taking my tiny boat out. Today, I returned from doing a reading in London at a Poets for the Planet event, to launch the Extinction issue of Modern Poetry in Translation Magazine. I stepped down from the train (to change at Oxenholme), ran across the rain, and what I smelt was the sea. It is balletic rain. A corps of rain. I just got back to Grasmere, walked up the curving lane, where William and Dorothy Wordsworth would have walked, past Dove Cottage, and I smelt it again. It is ocean water that’s falling. We are an 8-hour walk from the sea, 23 miles inland, but I feel like I am by it, on it almost, with this North Atlantic storm, these winds bowling themselves down the valley. If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow: and without trees, we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either. So we can say that the cloud and the paper inter-are. William and Dorothy Wordsworth made their own ink. The rain that fell in Grasmere. A long, thick feather from a wintering bird. These were the things that went into their hands and writing. Dorothy made many of her notebooks: loose-leaved, stitched, minuscule, so they could be taken out and written in and on with pencil, on tours of Scotland, or walks where her lines slope, curve off and undulate as much as the hills and desire paths. Outdoors, there are no neat, straight, restrained lines. These are field notes wandering off like drunks at the end of the night; swerving, in motion, sometimes scattered across the page, slumped, slant and angled. The lines went where her eyes went: crags and fells and lake edges. If we look into this sheet of paper even more deeply, we can see the sunshine in it. If the sunshine is not there, the forest cannot grow. In fact nothing can grow. Even we cannot grow without sunshine. And so, we know that the sunshine is also in this sheet of paper. The paper and the sunshine inter-are. Sometimes, the pages would be taken out and shared between the collaborators (perhaps in their urgency to each be working on the same moment simultaneously): Dorothy, William, Samuel Taylor Coleridge - their thoughts and phrases configuring and resurfacing like water birds in each of their different works in each of their different rooms; merging and shifting and echoing each other in ways that are more akin to oral tellings and retellings of events. Dorothy would test the quill and ink by writing amen. On some of the pages there is a visual Tourette's of amens interrupting and exclaiming amen amen amen... The changes that happened to the texts were referred to not as redrafts and edits, but as alterations. The analogy is one of clothes, collage, quilting, of hemming and repurposing. When you look at the notebooks, they do feel like a collage, with rough zigzag repairs, darker ink words added above crossed-out words, stubs where pages have been cut out, pastedowns and new paper flaps added for edits, Dorothy's writing next to Mary's next to William's next to notes added perhaps a hundred years later in pencil by their relatives. The manuscripts I held in my hands this week, are 50 yards from where they were first written 200 years ago, these notebooks were once cloth, rags, bleached and made into paper which still carry a tint of the old colour when held up to sunlight. The pages were worn once here in this place, a piece of The Prelude, a journal entry on shoulder or sleeve or newborn or shin, which in turn was once linen, which in turn was once flax plants, spun from the long fibers which grow just beyound the bark of the stems. The storm is now powerhosing the front of the house. It is late and I am wondering if they ever had rain like this: ink salt water, the affair-like scent of somewhere else entering their house. And if we continue to look we can see the logger who cut the tree and brought it to the mill to be transformed into paper. And we see the wheat. We know that the logger cannot exist without his daily bread, and therefore the wheat that became his bread is also in this sheet of paper. And the logger's father and mother are in it too. When we look in this way we see that without all of these things, this sheet of paper cannot exist. With immense appreciation and gratitude to Jeff Cowton, Curator and Head of Learning at The Wordsworth Trust: for exquisite ideas, inspiration, generosity, brilliant questions, time, and for showing and sharing the manuscripts with me, as well as Dorothy Wordsworth's pockets, on my first week in residence.

|

Author

Anna Selby is a naturalist and poet. Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed