|

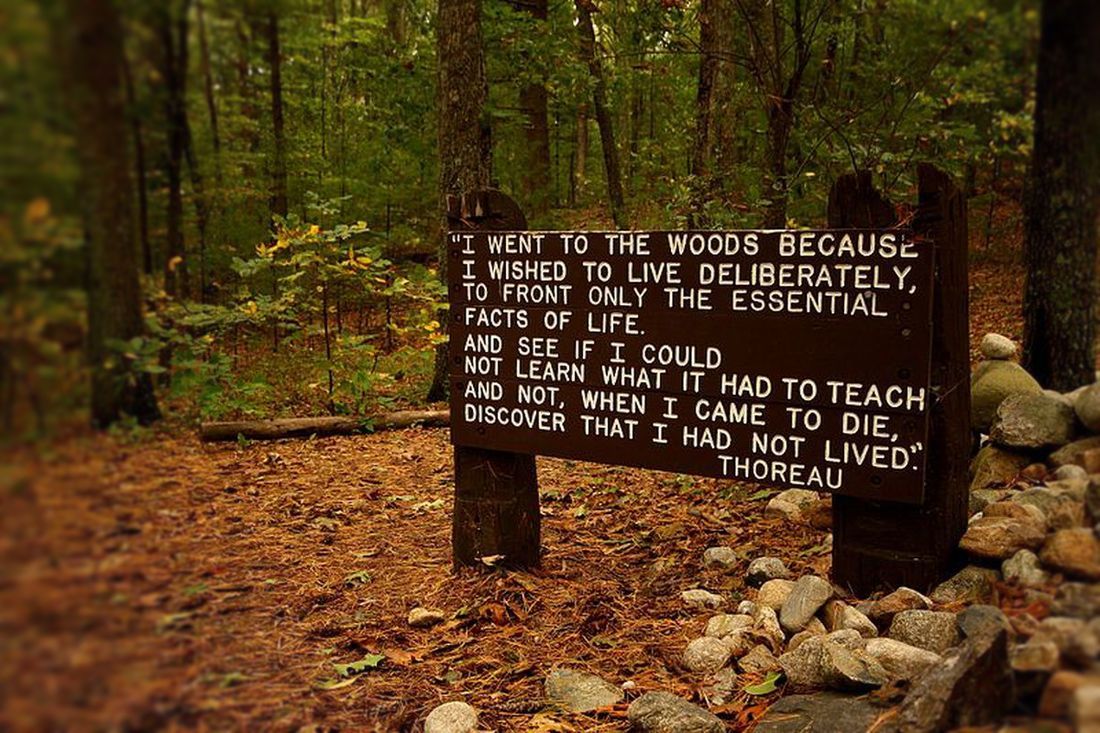

Yesterday, I saw one of the first salmon running. They remind me so much of the moment a plane levels off over the clouds. It came out of the water like an idea. That leap. I walked upstream and imagined it swimming beside me, past the jazz-like calls of coots and moorhens, under the leaves and weeds floating against it. I often keep watch for the first heavy rains in late summer and early autumn. I know that when these rains come, they’ll come - gathering at the foot of cliffs and mouths of estuaries. This is one of their signals to head home, to migrate. I watched them once, at dusk, on television, run, Atlantic Salmon are sea fish and Atlantic Salmon are freshwater fish. The scientific name for them is their prophecy, Salmo salar: salar, meaning to leap (from the Latin, salio) - and one of the terms used to describe them means, running upward, or up course (anadromous). They are born inland, they morph in the brackish border between saltwater and river, travel far out into the deep ocean, then, when they are about five, they return to the exact place they were created, to create new life. No one understands fully how they know how do this. They eat nothing on their trip back. They can jump up to 12 feet. Some have to travel almost 1,000 miles and climb 7,000 feet. In this shallow creek It is one of the greatest rituals of the year, to come and witness their migration. It is a tense drama though. A tragedy. I often wonder if it is the weaker swimmers I’m seeing attempting, then attempting again and again to jump the weir. There is a paparazzi of cameras pointed at them. An intensity of people trying to get a spot with their tripods. A warden keeping the number of photographers down and back. Once the fish have spawned upriver, many never make it back. Living In 1853, it was a perfect autumn. During the month of October, 165 years ago, the nature writer, Henry David Thoreau took Ralph Waldo Emerson’s children, his friends and family barberrying by boat, sailing at Fairhaven Bay and paddling on the Assonet and Concord river. While doing so, he constantly made notes in his journal about leaves. They astounded him that year, in a way they’d never done before. Each year, I make a pilgrimage to a different writer's house. In 2016, it was Thoreau’s home: Walden. I walked the route that Emerson and Thoreau used to walk together. I didn’t realise it at the time, but I walked one of Thoreau’s essays that day. It was my first Fall in New England. It was psychedelic, technicolour, inconceivable. I went around as if high: gawping and in awe. It was an Indian summer. I arrived on the date Thoreau’s essay began. The time of year, the weather, everything was identical to Autumnal Tints. I walked down aisles of leaves, a bird of prey followed me from Emerson’s house out along the streams and marshes moving from tree to tree. With each curve in the path, I had to stop to stare at a new sight of a tree. It was as if I were a bridegroom turning and it the bride. It was a huge American Elm that made me realise what Robert Frost meant by his yellow wood in The Road Not Taken. I grew up with a cherry blossom tree outside my bedroom window. As a child, I called it a blessing when you stood underneath and shook the branches, or walked under falling leaves. That’s what this mass death of leaves felt like to me: celebratory - a wedding, a carnival, ticker tape, confetti. How beautifully they go to their graves! How gently lay themselves down and turn to mould! They stoop to rise, to mount higher in coming years. The year’s great crop. They teach us how to die.’

6 Comments

|

Author

Anna Selby is a naturalist and poet. Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed